"Silver water. Golden rice" 1977 (Woodblock print, 36 x 46 cm)

"Fighting against drought" 1977 (Woodblock print, 44 x 57 cm)

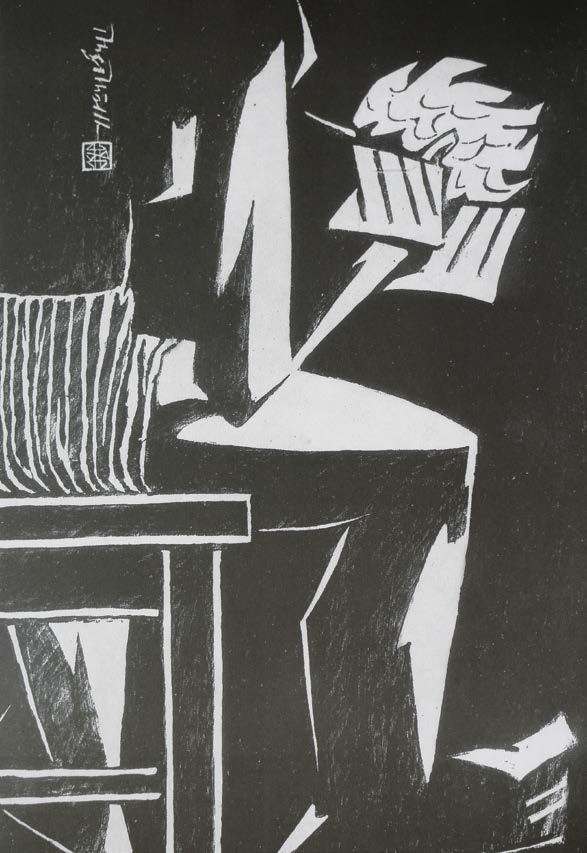

"Mountain class" 1983 (Woodblock print, 55 x 65 cm)

Woodblock print - The melody of Lines

Beginning in the 1970s, Phung Pham created a series of beautiful woodblock prints. Using only black and white, the prints had elements of simplicity and purity, brought to life by the intertwining melody of lines. These lines created melodies, rhythms, movement, lights, waves, and intricate decorative patterns within the composition, background, and localized sections. The lines shaped the form of the work, while the colors added resonance.

Phung Pham’s mindset regarding linear composition was flexible and open. It rarely repeated itself. Some decorative elements were derived from the texture of bamboo curtains, roller blinds, and wood grain, often featuring various floral and leaf motifs, reflecting the diversity of nature.

The uniqueness of these works can be attributed to the artist’s idiosyncratic sense of perspective and composition. Phung Pham explores various styles of composition: horizontal, vertical, frontal, diagonal, symmetrical, asymmetrical, and negative space. The same approach can be found in the realm of perspective, exploring manifold points of view, from linear, overhead, upward diagonal, to behind. Phung Pham creates the illusion of dimensionality in space through the interplay of light and shadow and the abstract utilization of ripples and waves. He explores both single and multi-dimensional space. Constant change and ever-evolving perspectives would later become a characteristic of Phung Pham’s lacquer painting period.

The creative process of Phung Pham adhered to a consistent visual language of his own, often referred to as “modernism” or “cubism.” This will be further explained later. This process underwent a gradual transformation in two stages: Throughout the first stage, spanning the 1970s and 1980s, his works were still closely tied to realism, following the aesthetic of traditional woodblock art, such as the pieces “Chong han” (Fighting against drought), 1977 (44 x 57 cm), “Nuoc bac com vang” (Silver water, Golden rice), 1977 (36 x 46 cm), “Di cho xuan” (Going to the Spring Market), 1980 (54 x 68 cm), “Ban nho” (Small mountain village), 1983 (69 x 49 cm), and “Lop hoc mien nui” (Mountain class), 1983 (55 x 65 cm). There was an unmistakable status quo much influenced by the sole dominance of Socialist Realism at the time. Exhibitions organized by the Fine Arts Association of the state mainly showcased works of this style, discouraging any divergence on the part of the artist.

However, during this period, Phung Pham quietly created a few pioneering and visionary works, such as “Ac mong” (Nightmare), 1978 (34.5 x 63 cm), “Vo de” (Untitled), 1986, (55 x 60 cm), which were early experiments using a modern graphic language, bold and a far cry from traditional aesthetics.

(continued below)

“Xam singing" 2006 (Woodblock print, 65 x 40 cm)

"Disappointed" 2011 (Woodblock print, 59 x 49 cm)

"Tear drop" 2011 (Woodblock print, 63 x 42 cm)

1986 was a milestone year of Doi Moi and Openness [1] in Vietnam, blooming amid the country’s widespread artistic freedom. By this time, Phung Pham was firmly on his own path, pursuing the artistic development that would characterize the subsequent stages of his work. This was a period of radical transformation in both his artistic language and beliefs. Phung Pham gradually incorporated cubism into the depiction of his subjects and themes. He began to abandon the imagery of realism. Lines became geometric and graphic. A prime example of this process is the series on the theme of transplanting seedlings: “Cay I” (Transplanting rice I), 1991, (46.5 x 56.5 cm), “Cay II” (Transplanting rice II), 1992 (46 x 56 cm), “Cay III” (Transplanting rice III), 1997 (60 x 49 cm), and “Cay IV” (Transplanting rice IV), 2008 (59 x 41 cm). The final piece was characterized by pure, abstract geometry.

In Phung Pham’s works, one can see the influence of Fernand Leger, Picasso, modern Western graphics and Japanese woodblock printing, as well as patterns from traditional costumes of minority groups and Dong Son bronze drums. Inspiration was drawn from everywhere and anywhere. Throughout the ages, linear composition and geometric design have always been fundamental in the art of mankind. What is essential in the work of Phung Pham, however, is his personal absorption and distillation of these elements into his own unmistakable style.

As mentioned previously, Phung Pham is passionate about the free play of creativity, discovering beauty in lines and forms everywhere. The quotidian aspects of daily life, ordinary and simple, can be found in his paintings: from harvest time, wheat threshing, rice pounding, and rice sieving, to setting sail, casting nets, studying, resting, and going to the market. With extraordinary attention to detail, he observes humanity with a tender compassion, always maintaining a deep love of his homeland. His work depicts a range of subjects, from wandering singers, traditional folk performers, and disadvantaged children, to elderly people and impoverished African immigrants. Phung Pham always empathizes with them and honors them in his creations. With increasing boldness, his lines gradually became rougher, stronger, and more angular. Decorative details gradually give way to abstract forms and shapes. Melody gradually gives way to rhythm. The works become more intense, powerful, industrialized, and well-suited to the breathless pace of modern times.

(continued below)

"Young girl and the flowers" 1983 (Woodblock print, 61 x 52,5 cm)

"Next to the flowers" 1989 (Woodblock print, 70 x 45 cm)

The most lyrically sentimental corner in his work is often dedicated to the themes of motherhood, love, and the beauty of women. In the exploration of these themes, in particular, the exquisite talent of the artist is revealed. Typical imagery featured the graceful curves of the neck, face, and fingers, flowing hair cascading over shoulders and spilling over a chair, the beautifully styled hair buns on top of the head, the elegant lines of the ao dai, and graceful postures and poses in glamorous costumes. The proportions here can be seemingly arbitrary, usually elongated, according to the artist’s own perspective, with skillful strokes, imbued with a sense of abstraction and decorative elements, reminiscent of Japanese woodblock prints and Egyptian frescoes. Indeed, they often carry a distinct flavor of the Orient.

Phung Pham’s works are truly diverse and multifaceted in emotional range. What always comes across is his love of beauty and humanity. On numerous occasions, he has depicted his own loneliness and inner turmoil in such works as “Suy tu” (Meditation), 2000 (62 x 43 cm), “Giot nuoc mat” (Tear drop), 2009 (63 x 42 cm), or “That vong” (Disappointed), 2011 (59 x 49 cm). Each work is an individual expression, concise and gradually abstracted within the black-and-white areas of the composition, playing with “black and white – light and dark”. However, it must be made clear that abstraction is not the ultimate goal or endpoint of Phung Pham’s art. For the artist, there is no end to learning. Like the shark, to stop is to die. Throughout the creative process, his artistic vision and expression are always broad, diverse, and constantly moving back and forth between traditional elements and modern extremes. As already discussed more than once, “continuous change while challenging his own perspectives are always key traits of Phung Pham through to the period of lacquer paintings later on”.

Bui Nhu Huong

Art Researcher and Critic

written in March 2023

[1] Doi Moi 1986: is the policy of economic reform and opening, breaking down subsidies, set by the state. Artists from here also have more freedom and openness in composing and exhibiting. So there is a flourishing and flourishing, forming an art movement “Renovation” in the late 90s.